Vapor impermeable surfaces on the interior side of exterior walls, e.g. showers–any difference between full-height vs partial height?

I have often heard that it is unwise to site a shower on an exterior wall, or follow the current trend of fully tiled bathroom walls, because the vapor impermeability of the interior surface can lead to condensation within the wall cavity.

Does this risk still apply if the interior surface of the wall is not completely covered, and the vapor impermeable material only extends up a partial height? E.g. for a soaking tub tile surround.

GBA Detail Library

A collection of one thousand construction details organized by climate and house part

Replies

Andy,

Any vapour-barrier works on a percentage basis, so if the wall cavities are unobstructed behind, the cavity will be able to dry to the inside proportionate to the amount of it that is covered by the impermeable material.

However if the walls are designed to dry to the outside (as most are), then the presence of these materials is only problematic when you are in a cooling climate and they could act as wrong side vapour-barrier.

Thanks Malcolm. I guess that does make intuitive sense.

Yeah, it does seem like this can be worked around with walls that dry to the outside. I was sort of struck by this notion when Christine Williams was remarking fairly adamantly in a BS and Beer podcast about it, and there did seem to be some back and forth between her and other architects who were in support of avoiding showers on exterior walls, but also felt like it was definitely something homeowners were constantly asking for.

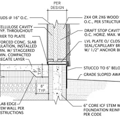

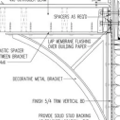

We need to be careful when thinking that walls dry to the outside. That works when the cladding includes a vented rainscreen, and that's certainly the preference for those who hang around on this site. But vented rainscreen claddings are by far the exception everywhere else. Most walls survive by accident because Tyvek behind vinyl cladding turns out to be very vapor permeable. With most standard walls, the sheathing is the least permeable layer and it is cold in winter, so there is real risk of the sheathing acting as the condensation plane. Adding moisture from a shower and stopping any drying to the interior is a recipe for disaster, as mentioned on the BS+Beer episode.

That said, I wouldn't be bothered by a soaking tub surround for all the reasons Malcolm mentions above. Plus, a soaking tub doesn't have the constant water application that a shower wall does. Not a problem. The biggest issue I see with tubs is that few builders pay adequate attention to insulation and air sealing below the tub deck. That lower wall must be insulated and made airtight before the tub goes in.

Peter wrote:

"The biggest issue I see with tubs is that few builders pay adequate attention to insulation and air sealing below the tub deck. That lower wall must be insulated and made airtight before the tub goes in."

Very true - and I agree with your advice about walls drying to the outside. I tend to make exactly the assumptions you point out.

I was thinking about this some more, and what if it's CLT construction? Then it wouldn't really matter, right?