Pros and cons of a “vapor open” exterior wall assembly with/without rigid sheathing?

CZ6A

Looking at a vapor-open exterior WRB like Solitex Mento. The claim is that it’s very “vapor open” to allow drying of the wall assembly to the outside. In a dense-pack wall assembly it can also be used without exterior sheathing, assuming your wall’s shear strength is looked after elsewhere.

Questions:

1. Vapor Open-ness. I understand the need for a wall assembly to dry, however, a big part of conditioning indoor air is humidity control. If an exterior wall assembly has a vapor open exterior WRB as well as a vapor permeable interior vapor retarder, can all this designed-in moisture movement create higher than necessary vapor drive resulting in humidity control problems? I worry about interior humidity in the summer and dry air in the winter.

Would a variable permeability WRB make more sense, rather than one that’s just vapor open?

2. Structure and settling. Would the lack of a solid sheathing material on the outside of the wall assembly somehow compromise the wall structure in any way? Would it be any better or worse at preventing the settling of dense packed cellulose?

3. Sound. I’ve done quite a bit of reading about STC ratings of different wall assemblies. Adding mass by adding layers of drywall is a great way to improve the STC rating of a wall assembly. Knowing this, what’s the impact of removing the exterior sheathing from a wall assembly and replacing it with a fabric WRB? In my case, I’d have a 12″ double stud wall where the only sheathing would be the drywall on the inside (racking provided by metal T bar).

GBA Detail Library

A collection of one thousand construction details organized by climate and house part

Replies

I am somewhat skeptical of the idea of having a WRB without anything solid underneath it, but I'll discount those reservations for my answers.

1. Provided that the drywall is intended to be an air barrier and detailed properly, vapor drive is unlikely to be a problem. I think there is an article about it up on this site somewhere, but air flowing freely carries far more moisture than the vapor that drywall or other materials can transmit. If you are really concerned, you can use a latex paint on the drywall. *Edit:* On second thought, I can imagine scenarios where the summer weather causes problems, so I'll defer to another poster with more experience in that area.

2. This depends on the specific properties of your WRB and its propensity to warp under long-term stress. I doubt it will ever perform better than solid sheathing in that regard though. You'll have to ask the manufacturer.

3. If you have 12" of cellulose you are unlikely to have sound problems of any kind, regardless of sheathing. The dense-packed cellulose is a lot of mass.

作为额外的注意,我推荐看看布鲁里溃疡ilding Science Corporation's suggestions for double stud walls here:

https://buildingscience.com/documents/enclosures-that-work/high-r-value-wall-assemblies/high-r-value-double-stud-wall-construction

Having a layer of plywood on the outside of your inner wall is an excellent, durable way to provide an air barrier and take care of bracing, and you can reserve the space between the studs as a service cavity if you so choose. In your case, you would be able to omit the exterior sheathing in favor of your WRB.

To clarify my earlier edit: My main concern with your assembly is not that it would disturb your interior humidity, but that it is susceptible to water damage.

For one, it would be difficult to detail your WRB as an air barrier (sheet goods are usually preferred for that job; they are more durable, more reliable, and easier to detail). During the summer, it is quite likely your air conditioner will cool your drywall, interior studs, and several inches of cellulose below the dew point of the outside air. If the exterior is not air sealed, then humid summer air can flow into the cavities and deposit moisture on your cellulose, studs, and interior sheathing/drywall. This would quickly lead to water damage. Even in the winter, air flowing into the cellulose will reduce the insulating performance of the wall.

Supposing your WRB is properly detailed as an air barrier, it is still *theoretically* possible that it could let too much vapor into the cavity, leading to the same kinds of moisture damage I mentioned earlier -- but this is beyond my area of expertise. Someone more familiar with how permeability figures work would be able to advise you better on that. I imagine this is a bigger concern when the interior is less vapor-permeable than the exterior.

If your reluctance to use additional sheathing stems from a desire to preserve your wall's drying potential as much as possible, I believe your efforts are misguided. It is far more important to have a properly detailed air barrier on both sides of your double stud wall than it is to leave it as vapor open as possible. If the air sealing is done right, drying potential in one direction is more than enough to keep the wall in good shape. If you follow Building Science Corp's recommendations, it is hard to go wrong.

Hi Aedi, thanks for your replies!

In my case, I have an interior load bearing 2x6 wall with steel T bracing for shear resistance and an exterior 2x4 wall.

I was looking at WRB products on 475's website and came across Mento, remembering I'd seen several builds where it was used in dense-packed walls without sheathing. My primary Air Barrier will be at the exterior, with my Vapor Retarder on the inside of the 2x6 wall. I will also have a 2.5" service cavity on the inside filled with fiberglass.

I've seen BSC's favorite Double Stud wall assembly before. I don't doubt its durability, but the main reason I don't like it is due to it needing insulating from both inside and out. This almost doubles the labor involved with dense packing the wall, doubles the cost of the netting, and doubles the cost of sheathing (assuming exterior sheathing is still used). It is also a challenge to dense pack walls from outside on a two story house, requiring scaffolds or a lot of moving ladders/platforms around. I would MUCH rather insulate from the inside only.

Another challenge is bay-to-bay dense packing. In my more traditional double wall I plan to staple netting between the stud bays, making it much easier to hit the 4+ lbs/cuft target required to eliminate settling concerns. The BSC wall has a continuous layer of sheathing on the inside of the 2x6 wall. I guess netting could still be stapled to the sheathing between stud bays.

Another thought was budget. Solitex Mento is not an inexpensive product, but if it's being used in lieu of Zip sheathing it actually comes out way ahead on cost.

Oh, and with respect to the summer humidity condensing on the interior surfaces, with the 2.5" insulated service cavity on the inside, I don't believe that will be a concern.

That is only true if the service cavity creates an air barrier. Otherwise, the outdoor air can easily flow through the cellulose and into the fiberglass and still condense on the drywall and studs.

Sorry, I should have clarified the location of my vapor retarder. My proposed wall assembly is as follows, outside-in:

1. Exterior air barrier (taped sheathing or membrane).

2. 12” double stud wall (2x4 exterior, load bearing 2x6 interior) dense packed with cellulose.

3. Interior air barrier/vapor retarder (Intello or poly).

4. 2.5” service cavity with fibreglass batts.

5. Gypsum wall board.

The service cavity being insulated will keep the vapor retarder at a higher temperature than the interior on hot humid days. Our dewpoints don’t get much higher than 77F here, so with the interior at 72-73F there’s a pretty small window of concern, and 12” of cellulose to buffer moisture.

That’s my thinking anyway. This is why my original concern over a wall that’s too vapor open. If large quantities of 77F fully saturated air were to contact a 72F vapor retarder, there might be a problem.

In theory, my R10 service cavity would keep my vapor retarder at about 73F (R10 / R54 x 5F delta T), reducing that 5F window to 4F. If I can make sure to limit vapor drive through the assembly I don’t think there’s much to worry about.

Unless I’m missing something?

So your total wall thickness is 14.5"? And you might call it a triple wall, from outside to inside you have 2x4s, then 2x6s, then 2x3s? Why not make your 2x6 cavity your service cavity, and if you like make the space between the outer 2x4 wall and the inner 2x6 wall a little deeper?

Ah, I understand the assembly better now. Yes, that assembly should work to my knowledge, and has a good amount of redundancy built-in.

I have to reiterate and agree with Charlie though, there is really little reason to not make the 2x6 wall your service cavity. It might seem like more room than you need for wiring, and it is. But there are other services you would be able to put in it, like your plumbing and any vents you may need. You would also be able to create inset shelves in empty service cavities by installing drywall on and between the studs, or build in seating/other forms of storage.

很清楚,我认为Aedi和查理are suggesting as an alternative wall assembly is:

- Cladding

- Rain-screen strapping

- Sheathing or Robust WRB

- 2"x4" exterior framing

- Gap

- Interior variable perm membrane or poly

- 2"x6" load-bearing wall (insulated or not) as service cavity

- Drywall

I'd suggest:

- Make the interior wall 2"x4". If the wall is inside all or most of the insulation, there isn't much advantage to using 2"x6".

Hi Lance,

To clarify, you are intending to use the Mento WRB and your interior vapor retarder as air barriers, correct? If done with care, that should keep your assembly safe from the bulk of the danger. It would be nice if someone with more knowledge on permeability could assuage my concerns on allowing too much vapor transmission into the cavity, but I do think it is unlikely to be a problem.

Your assembly does sound interesting and perfectly doable, but I think you can safely incorporate some of the details from Joe's wall while avoiding the pitfalls you mentioned. Namely, because you are planning to leave a 2.5" fiberglass-filled service cavity anyway, I would just increase it to the full 5.5" of the stud bay and use plywood as an air/vapor control layer. This ensures that the interior air barrier won't be punctured by electrical boxes or careless future homeowners. It also eliminates the need for netting and T-braces. I believe there would still be ways to blow cellulose into the exterior cavity from the inside, though that comes down to specific construction details.

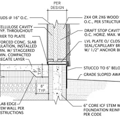

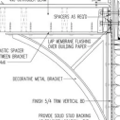

字符lie, Aedi and Malcolm, I will continue down here for sake of clarity while posting a picture of what I have going on and the reason my main wall is capped at 12" deep. See attached image.

What you're looking at is an 8" poured foundation wall, shown with 2" of interior and 2" exterior above grade insulation + exterior fiber cement panel. The sill plate is a 2x4 ripped down to 3" wide supporting the first floor assembly.

On top of that is my load bearing 2x6 wall, which must be flush with the rim board (shown through a window section with 2x3 cripple studs). The planned location for my vapor retarder is on the inside of that wall. Not shown is the 2x3 service cavity that will be inside of the vapor retarder and filled with fiberglass, nor the T channel on teh inside surface for shear resistance.

The exterior wall has a 2x6 bottom plate ripped to 4.5" wide, supporting the 2x4 wall that bears 2" over the concrete foundation wall. 1/2" sheathing is shown on the outside, but can also be a membrane WRB per this discussion. Not shown is exterior strapping for a ventilated rain screen or siding material, that would sit proud and shingle over the exterior foundation insulation with a piece of metal flashing attached and sealed to the the bottom plate to direct rain water outboard.

Making the wall thicker is not possible without pouring a thicker foundation wall and/or reducing the 2" bearing of the outer wall on the foundation. I have designed it this way to eliminate the considerable thermal bridging normally found with having floor system that extends to the outer limit of the wall assembly. My design came after researching balloon framing and Swedish platform framing.

I do not wish to invest in exterior insulation as foam is expensive, delicate and difficult to work with, and Rockwool Comfoboard is prohibitively expensive.

Now the suggestion of the BSC double stud wall.

Adding a layer of sheathing inside the wall assembly would require dense packing from both outside and inside the wall, a difficult task on a two story house. It would double the labor and material cost of sheathing and netting, and nearly double the labor to blow in the insulation. Detailing the interior sheathing as an air tight layer would likely need to be done prior to the exterior wall being erected, lest you be working tapes and adhesives around and between the two wall structures. On paper Dr. Joe's BSC double stud wall looks great, but I see some challenges with building it as well as some unnecessary costs.

My design can be built very easily, with the exterior 2x4 walls going up first followed by the interior 2x6 walls, joined at the top by a continuous bridge of 3/4" thick 12" wide plywood. The 2nd floor goes up as it would in any conventional house, supported by the 2x6 wall, then 2nd story walls in the same order as the first. My original plan was to support the 2nd floor with a ledger board, but my Engineer talked me out of it.

So, thoughts? Have I missed anything?

One last thought. I know cellulose is treated with boric acid and is a pest deterrent, but how pest/insect resistant would a product like Solitex Mento be? Any cause for concern? Any better or worse than OSB/Zip?

I appreciate your thoughts and input!

Lance,

I think it d0es a lot of things quite well. I'd skip the inner service-cavity, because especially when the membrane or poly are that far in, it makes no difference to the air-sealing, and in general I think they are a solution in search of a problem. But that aside, its a wall I'd certainly consider using.

One small thing - as you are building it yourself - I'd consider using two bottom-plates on the outer-wall. Trying to stand them and squaring everything is a lot harder than setting all the sill-plates then just nailing the bottom-plate of the framed wall to the sill-plate. I always do this on garages. Saves a lot of headaches.

I'm afraid my local inspector (Ottawa Ontario) will insist there's a vapor retarder installed. That's the impression I'm under anyway, and after reading a few of the (very helpful) articles linked to, the inner vapor barrier has the potential to really help with moisture intrusion into the wall in winter, as was the case in several of the tests.

Excellent tip for the additional bottom plate! I need to make sure I have the same number of horizontal plates in my outer and inner wall assemblies to equalize shrinking, so if an extra plate is necessary (or possible) I know where it's going now!

Much appreciated!