Rehab insulation issue

Greetings and thanks Martin in advance for your help…..

I am doing a rehab in the Chicago area….exterior wall consists of a thin firebrick mortared to a 6″ block with plaster on the inside. I have stripped the inside down to the block and am framing 2″ off the block with the plans of spraying 2″ of continuous closed cell on the block with cellulose over that in the stud bays. Hoping the closed cell would take the place of tyvek along with the obvious.

My insulation contractor says waste of money simply do all open cell.

Looking for your direction please.

Phil Ternes

Consor Development

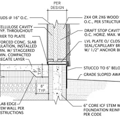

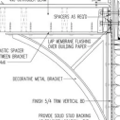

GBA Detail Library

A collection of one thousand construction details organized by climate and house part

Replies

The 2012 IRC specifies closed cell foam for flash and batt. But I will be curious to read Martin's advice when installing against an above-grade block wall.

From my research, you have the right approach. When I was working in Chicago, that's essentially how we'd did renovations to commercial brick buildings, (but with steel studs, and no cellulose, because it was commercial). In climate zone 5, you want closed cell foam. Building Science Corporation has a whole bunch of articles on this approach, as well as some non-foam options if that strikes your fancy:

——标准泡沫选项,以及non-foam option appropriate for your climate zone in "Figure 9":https://buildingscience.com/documents/building-science-insights-newsletters/bsi-095-how-buildings-age

- More details:https://buildingscience.com/documents/bareports/ba-1505-measure-guideline-deer-interior-insulation-masonry-walls/view

- Even more details:https://buildingscience.com/documents/insights/bsi080-tailor-made

Those articles should address the work you need to do on the exterior of your building somewhat as well. The important thing is that you want to make sure your brick is in good shape and all your flashing details are up to snuff. If you insulate the interior of a masonry building without making sure you've really dealt with your rainwater management, you can get into big trouble with freeze-thaw damage.

Ideally you'd leave a 1" gap between the block and the next layer as a capillary break and a channel for the (now colder & wetter) block to dry into. Even a half inch is better than nothing.

At the same wall thickness as the 2" spray foam + studwall, a half-inch gap (use strips of half-inch foam board as spacers) and 1.5" of Thermax rigid foam with a 2x4/R15 rock wool studwall would meet code-min performance for zone 5A, and would likely come in subtantially cheaper than 2" of closed cell polyurethane sprayed directly on the block.

Dana,

All of BSC's recommendations on insulating masonry walls from the interior emphasize getting the insulation tight up to the brick, regardless of weather they are using spray foam, rigid foam board (which they basically suggest you glue to the brick), or cellulose + smart vapor retarder.

If your brick is particularly lumpy and you're not using spray foam, they even recommend doing cement render over the brick to level it out before applying a fluid-applied, vapor-permiable, waterproof layer.

Why do you prefer leaving a gap between the brick and the next layer instead?

*Because it's the internet and tone is hard, I'm trying to learn, not be confrontational! :)

Brendan: Most (but not all) brick walls are cavity walls. With a thin-brick mortared to the block the risk of frost damage to the exterior finish goes up when there is no drying channel. The hardness of that exterior brick would need to be assesed before building with the foam tight to the CMU.

I see. The BSC articles seem to focus on solid multi-wythe solid brick walls, not brick and block cavity walls. Those solid brick walls were also what I was thinking of in the commercial renovations I worked on in Chicago.

Am I understanding right that that difference (the solid brick in the BSC articles vs brick and block that Phil has) is the reason your recommendation is differing from the BSC articles?

Or is it more that if he has low quality brick on the exterior, the foam tight against the brick is too risky?

BSC has an article about "good" brick and "bad" brick, but I'm not sure how helpful it is to answering the original question here unless Phil wants to send a brick to BSC to get tested:https://buildingscience.com/documents/insights/bsi-047-thick-as-brick

One thing from that article that is worth noting I think is that the less rain hitting the brick the safer insulating it is. So bigger overhangs would mean insulating the brick is safer.

Phil,

The basic answer to your question is that closed-cell spray foam is preferable to open-cell spray foam.

My own instinct (which isn't based on direct experience) is that it should be OK to install the closed-cell spray foam directly against the block wall, unless there is evidence of an obvious moisture problem or water-entry problem. I doubt that the thin firebrick that is mortared to the block wall is as susceptible to freeze-thaw issues as old porous bricks (the kind sometimes used for multi-wythe brick walls).

thanks guys for the constructive banter...greatly appreciated....more data points now

there was a 1" gap between the block/brick and the plaster and I was told yesterday by the owner that he repainted often to cover up water spots on the walls....and there are no apparent leaks

I now think I should keep the airspace and use the method suggested in #3 above???no doubt the walls were not drying at an appropriate rate

Or....what about blowing cellulose in the entire cavity right up against the block? since it wicks water and exchanges humidity so well?

Help again please,

Phil

There are some people in NYC who have done OK with cellulose dense packed right up tight to solid multi-wythe brick walls, but that's zone 4A, with far fewer hours below freezing than in zone 5A.

的核心是砌块墙完全灌浆或filled with concrete, or are they empty?

Phil, if you want to blow cellulose directly against the brick, but are leery of the risk your slightly colder climate has compared to New York that Dana mentioned, you could try the BSC method, which is to use a fluid applied, vapor permeable, waterproof membrane against the brick, blow in the cellulouse, then use a smart vapor retarder on the inside. This might get you the best of both worlds, in terms of allowing the brick to dry towards the interior, but also reducing the amount of interior moisture that makes its way to the brick.

Essentially, it's an adaption of the New York cellulose approach for colder climates.

The method is briefly outlined in Figure 9 of the "How Buildings Age" article I linked above.