Cold Sheathing Concern

I’m in Maine, zone 6 and I’d like to utilize the following wall detail and would like some suggestions, from the inside out:

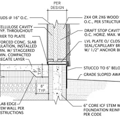

– Airtight drywall approach, Double stud wall, inside wall 2×4 @ 16″ o.c., 3.5″ gap, outside 2×4 stud wall at 24″ o.c., 10.5″ total thickness. Insulate with Roxul batts. CDX plywood sheathing with taped seams. Tyvek Drainwrap followed by Certainteed fiber cement board clapboard siding.

我担心的是寒冷的防潮问题。我想minimize future mold issues while keeping my cost and labor down. I am a DIYer so I’d prefer to install Roxul batts over dense pack cellulose which I understand doesn’t slow air movement. My initial plan was to utilize zipboard as my exterior air and WRB barrier but I’m concerned with the untreated OSB interior face, was I right to be concerned or can I go back to using zipboard? I’ve seen several projects done this way, how are they handling condensation on the OSB zipboard?

Thanks in advanced!

GBA Detail Library

A collection of one thousand construction details organized by climate and house part

Replies

Brian,

I'm designing around similar concerns. I have chosen to place the sheathing (plywood so if it does ever get moist it'll survive) on the outer face of the inner 2x4 wall and frame both 24" OC and aligned. I'm sticking with 24" OC framing even though my snow load requires that I use doubled studs in the inner (load bearing) wall. Aligned framing reduces, to the point of elimination, any concerns over possible wintertime condensation . With the sheathing positioned as I have it is much warmer, eliminates the need for airtight drywall and provides a "service cavity".. There really is no need for exterior sheathing, but if you must I'd recommend the use of fiberboard. By using Roxul comfort bats that are intended for use with steel studs, for the middle layer, they neatly fill the spaces behind the outer wall studs.

To answer your questions, IMO you are right to be concerned about moisture issues and the projects you've seen using OSB on the outside are simply ignoring or unaware of the danger.

Jerry, placing the sheathing on the outside of the interior studs is an interesting solution that I might like to pursue. With this approach, where is your WRB and what is it attached to? Does it span between the exterior of the outside studs and then your siding over it?

Brian,

Exactly, you have the picture, after the insulation is installed, the house wrap is attached (stapled) to the studs then the exterior finish material spans from stud to stud over the house wrap.. The house wrap is the WRB and prevents wind washing of the insulation but it is NOT the primary air barrier. I didn't mention that the plywood is the primary air barrier and must be caulked, taped & otherwise sealed accordingly. Again I'll emphasize that using aligned framing, though it may cause slightly greater heat loss, essentially eliminates any condensation possibility.

I have a hard time understanding why the "cold sheathing" issue would be any more likely with a double (or generally thicker) wall design than in a code-minimum wall. In either case, the exterior sheathing, outside of the insulation layer, will be fairly close to outside air temperature, unless exterior foam is applied for that purpose. Making the wall thicker just retards the heat flow without having a dramatic effect on the temperature profile. One should not really want the sheathing, if on the outside, to be "warmer" to avoid condensation issues, except by placing insulation outboard of the sheathing. If the sheathing is right under the siding, warmer would mean higher heat loss,

One of the things noted in what I think was a BSC report on different wall designs was that concerns about condensation on "cold sheathing" go away if there is something done at the interior to isolate interior air from the wall cavity. ADA does that.

Dick,

The concern is miss labeled, it's not cold sheathing it's WET sheathing. Why is there sheathing? To provide shear or racking strength and almost incidentally to stop air flow. A double wall is not conventional any way , why should the sheathing be located on the outside? If it is located as I've suggested it can serve it's purpose (s) and have most of the insulation on it's outside WITHOUT FOAM! With sheathing positioned so that 2/3 or more of the thermal resistance is outside of it and 1/3 or less inside it will be above the dew point even with an outdoor temperature of -20f while the indoor temperature is 70 f at 40 % RH! ADA is expensive to implement properly and only lasts till a homeowner hangs a picture or 2. While a properly detailed air barrier at the sheathing is less costly and far more durable. If the BSC article did actually say the condensation issues with cold sheathing go away with ADA the conclusion is simply WRONG the concerns may not be as great but there is still a condensation probability. It is simple physical reality that warm air holds more moisture, as that air is cooled moisture may condense.

Brian,

In case you haven't seen it, you should probably read"How Risky Is Cold OSB Wall Sheathing?"

If the double-stud approach worries you, you can always go to a conventional stud wall with some of your insulation installed on the exterior side of your sheathing. Although this approach usually requires rigid foam, some builders install mineral wool insulation on the exterior side of their wall sheathing.

Jerry,

How are you intending to handle framing out and flashing your windows? Are your windows innies or outies?

Martin, using exterior foam insulation is a good solution and I admit its a better design, however it proved to be far too expensive and labor intensive for us.

Brian,

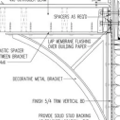

I'm resigned to a bit of wood thermal bridge at the windows. There will be a "box" of 3/4" plywood connecting the inner and outer framing and sitting around each window. I intended to position the windows near mid wall ( which can be shown is best for thermal performance)) but attach them to the inner wall with "mounting straps" that will be covered by interior jam extensions.

I don't know if this should be called "innie" but it's certainly not "outie". On their insides, the windows will be caulked, gasket-ed and sealed to the plywood box which is a continuation of the sheathing air barrier. The house wrap will wrap around the head and jam , under the outer face of the windows which will be caulked to the house wrap. Also I'll have a sill pan that goes from under the window out over the exterior finish material. The exterior finish material (thin brick) wraps around the jams and is used to make a sloped sill while at the head there is a flashing with a 'drip edge'. The windows are also caulked to the exterior finish material. BTW I think it's WRONG to even think that exterior foam is a "better" design! Exterior foam is more accepted and usual but certainly not better than well thought out double walls! Without question double stud walls can return more actual thermal resistance per $ for every square foot. It is also likely that moisture issues are better dealt with by double walls than by exterior foam as it is relatively easy to assure drying both ways with double stud designs while foam often blocks drying ability. In fact I can't think of a single attribute of exterior foam that is actually "better" than double stud & if one is pointed out I'll reverse it as well!

No matter what you do for insulation, building a rainscreen-gap between the clapboards and sheathing with 1x furring allows even cold sheathing to dry toward the exterior (yes, even in winter.)

Using 2' overhangs on the eaves & rake of the roof reduces bulk moisture penetration of the clapboards exterior by at least an order of magnitude, maybe even two, which will also keep the sheathing much drier.

Rather than Roxul for cavity fill, cellulose or cotton will manage wintertime moisture drives far better than any mineral or glass fiber.

In US zone 6 climates Robert Riversong is able to get away with double-studwall/ & truss wall designs of ~12" of roof overhang per story, cellulose for cavity fill using only ship-lap wood siding on the exterior, no sheathing. I'm not a fan of this approach since it requires near-perfection on many of the details, but it works (or seems to- sample size is small and history is well under 5 decades.) Rainscreened clapboards on sheathing seems inherently more resilient against construction faults and maintenance neglect over time, though it's more expensive, to be sure.

I've built several houses with zip system, double stud walls, and dense-pack cellulose (DPC). No problems yet. I have been searching for the elusive "cold sheathing" failures myself for years and think it's something of a myth. If anything the cellulose should be safer - if indeed there is condensation, the DPC should be able to handle and diffuse the moisture. And agreed that the rainscreen/air gap is the critical element.

I may be moving away from zip - the only thing I ever liked about it was the ability to tape the seams, but there are plenty of tapes on the market that I would be comfortable using on Huber's regular advantech sheathing, which I think is a much better product.

I am also in southern Maine (and wrote a piece on a similar project for JLC I could e-mail you).

Dan,

Thanks for the note, yes, please forward the link to your JLC article, I'd love to read it.

我的问题是我希望绝缘卧室uld be a DIY project and I do not have the ability to DPC (I don't suspect the big box rentals are adequate for DPC). This is my justification for going with Roxul as even a dub like me can install it. Also, I was hoping that my wrinkled house wrap (DrainWrap) could serves as my rain screen to avoid putting up a million pieces of strapping. Is this a risky approach?

So in summary, Cement board siding on Dupont Drainwrap on 1/2" plywood taped as primary air barrier. Cavities insulated with Roxul and a second air barrier either at the drywall (ADA) or on the outside of the inside studs (MemBrain or taped plywood). How risky is this wall detail?

Dana,

"Rather than Roxul for cavity fill, cellulose or cotton will manage wintertime moisture drives far better than any mineral or glass fiber. "

Exactly what does this mean? What moisture concerns are there with drying in both directions? What do you base the assertion on? Can you point to ANY evidence of an actual problem with using mineral wool? Several things argue for the mineral wool, it is no more costly, is easily done DIY or with minimum wage help, it offers greater thermal resistance., in many areas competent dense pack installers competent and experienced packing 'deep cavities simply aren't available.

Brian,

Without question a drainage plane is a very good idea. I think you should consider one or 2 more options, both with plywood on the outer face of the inner wall as the primary air barrier. The options I'll describe include a drainage gap created by furring strips under the siding and over ordinary house wrap, but if you are really confident in drain wrap you could use it instead of the furring over ordinary house wrap. . Option one, use exterior fiberglass-gypsum sheathing (Denseglass or equivalent) covered by a vapor open house wrap then furring strips parallel to the studs then the fiber cement siding. Option 2 same as one but replace the fiberglass- gypsum with fiberboard. Both of these materials are quite vapor permeable (10 perms +) . Either fiberglass-gypsum or fiberboard is less costly than plywood. The least costly is fiberboard which also adds r 1+ to the wall's thermal resistance.

Jerry: Bulk water gets by clapboards from the exterior, and often the flashing, whether you see it or not. If it can't drain or dry to the exterior quickly , it ends up in the sheathing. I can't stress enough how much resilience even 1/4" of rainscreen gap adds to the structure.

与纤维素腔填充th的湿负荷e sheathing is shared by the cellulose, which can tolerate a significant amount of moisture without degradation or loss of function. The wicking characteristics of cellulosic fiber distributes the load over a wider area, which adds to the resilence. With mineral or glass fibers, not so much- all of the moisture stays in the decking until it can dry (pick direction, doesn't matter, it's bound in the wood until it can find it's way out.) Minor air leaks from the interior during winter months will also deposit all of it's moisture in the sheathing if the cavity fill can't buffer it, but the sheathing is significantly protected with cellulosic insulation.

There are 1000s of examples of wood sheathing with high moisture content with glass & mineral wool insulation- you really need me to dig it up? This has been studied extensively and modeled VERY well by the folks at the Fraunhofer Institute, (the developers of the WUFI moisture transfer modeling tools for building assemblies), as well as many many other places. Sure, I could probably point you to 10,000 examples of "...evidence of an actual problem with using mineral wool...", if you really need it, but in almost all of those cases it's arguable (correctly) that the primary problem was bulk-water intrusion or air leaks or both, with the insulation being the innocent bystander.

It's not a matter of the rock wool being a problem, but rather of cellulose lower the risk of problems by making the assembly more tolerant of imperfection. It's a "good-better-best" sort of thing that takes into account the reality that there's no such thing as "perfect", especially over the lifespan of a building. Rainscreens add to first-cost, but you're buying resilience. It's a similar story with cellulose.

Rock wool batts can be a DIY install, sure, but it's also quite difficult (some say impossible) to achieve the same quality of full-fill as a blown fiber solution- there WILL be gaps, voids and compressions, it's only a matter of degree. A dedicated DIYer can easily beat the batt-installation quality of a "time is money" contractor, but even a sloppy dense-pack job is going to have fewer voids. And in a wall assembly that is rain-screened on the exterior the seasonal moisture cycling will be lower, which means settling due to under-density packing will be far more limited than in an assembly without a rainscreen.

Also I'd like to clear up a misunderstanding by Brian in his initial post:

" I am a DIYer so I'd prefer to install Roxul batts over dense pack cellulose which I understand doesn't slow air movement."

Absolutely FALSE!

Cellulose and Roxul BOTH slow air movement (and by quite a bit!), but dense-packed fiber slows it far more than any batt solution. During installation the fiber is carried along by the blower air all the tiny leak points, where it plugs them. The is a huge performance distinction between open blown, loose fill or damp-sprayed cellulose where the cavity is not filled under high air pressure. But even 1.5lb loose fill cellulose is more air-retardent than standard density rock wool batts, though probably not as air-retardent as high-density rigid rock wool (though I've not seen data on that.)

What dense packed cellulose isn't is a PERFECT air barrier (though it's pretty close at 3.5 - 4lbs density), and can never replace caulking & sealing the mechanical elements of a wall or roof assembly. But in comparison to stacking layers of rock wool batts in a double-wall dense-pack is literally orders of magnitude tighter against convection currents & infiltration currents coming through the fiber.

Thanks for the thorough assessment Dana - I might need to take another look at DPC.

Dan: Being from Southern Maine, can you recommend a insulation contractor familiar with DPC?

Thanks!

Brian - there are several. We work with I&S. Horizon Residential are old friends as well who have been doing more DPC in the past couple of years.

Dana,

Thank You!

Now one more question. Roxul comfort bats start out at r 4.28/" dense packed cellulose is usually described as r 3.8/" . Is the performance loss due to the "imperfections" in the installation of bats ever going to degrade the result (whole wall) to what cellulose would yield with the same cavity depth?

As you know I plan on using plywood sheathing on the outer face of the inner wall and doing all I can to air seal it. I do believe this essentially eliminates the cold sheathing concern regardless what is used for insulation. With NO exterior sheathing, only house wrap and a drainage plane outside the house wrap, It seems to me that the moisture holding property of cellulose is less desirable than the drainage properties of mineral wool. However, the walls I intend to build will have 3/4" fiberboard as exterior sheathing, the house wrap then drainage plane then exterior finish material, The fiberboard acts much more like cellulose, which it's made out of, than plywood or OSB in that it can absorb lots of moisture yet dry easily. Is Roxul a real or theoretical risk?