Framing a ceiling service cavity

Planning stage of a new construction… I’d like some input and suggestions on the best way to frame a service cavity in the ceiling. Here are the pertinent planned details of the house…

Simple rectangle with 51’6″ x 40’6″ rough framing dimensions (exterior).

Trussed gable roof with a single ridge running the length of the 51’6″ dimension. Raised heel trusses for insulation. Truss span will be 40’6″ with no load bearing in between.

Vented unconditioned attic. No ducts or mechanicals in the attic.

2×6 exterior walls with liquid flashed ZIP sheathing for an air barrier.

So my question(s) is this…

Once the trusses are in place, I want to attach ZIP or OSB to the bottom of the bottom truss chords to create the air barrier and then create a lowered ceiling below that. Is this practical? Does it make sense to use drywall here instead of OSB for the price?

What’s the (a)best and (b)most economical way to frame the lowered ceiling in this situation that will support the drywall while ensuring the integrity of the ZIP / OSB air barrier above?

House will likely use ductless mini-splits (possibly ducted if service cavity is used) so the primary purpose of the service cavity would be for ERV ducts. Is there a better method for this?

I suppose a better question might be…is the added cost of building a service cavity worth it if all I need is space for ventilation ducts? Would small soffits only where the ducts are needed make more sense?

GBA Detail Library

A collection of one thousand construction details organized by climate and house part

Replies

Jason,

Use Simpson clips. A wide variety of clips are available in the Simpson catalog. Just make sure that the clips are attached to something structural. For more information (and photos), see this article:"Service Cavities for Wiring and Plumbing."

Martin,

Thank you for the quick reply.

Jason,

A service cavity deep enough for ERV ducts, so that they can travel in both the direction of the framing, and across it, takes a lot of space. It also necessitates framing higher walls to achieve a reasonable ceiling height. When finished the vast majority of that 2000 sf cavity will be empty, or at best have a few wires running through it.

Why not do a duct layout, look at where you can include bulkheads or small dropped ceilings, and see if you can avoid what is a large effort for something that doesn't serve much purpose?

Malcolm,

Very good point. As you can tell from the very last part of my initial post, the more I thought about it, even I as I typed the questions, a full service cavity seemed like too much. I'm going to take your advice and layout the needed ducts and look at a "smaller scale" solution.

Jason,

Try and make them features. A bulkhead with thickened walls on each side can frame a niche for a sideboard, sofa, or bed. Dropped ceilings can provide opportunities of recessed lighting. If they look deliberate and are integrated, they can enhance the interior architecture.

You can also hide ductwork and wiring in coffered ceilings, and that gives the opportunity to use valence lighting (reflective lighting), which can give interesting visual effects. Soffits above cabinetry is another possibility. Be creative. It’s almost like building secret passageways in your house :-)

Bill

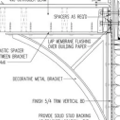

On a couple of recent projects we did what you describe--zip sheathing attached to the bottom of the roof trusses, taped for the air seal, and then 2x4 strapping on edge 24" OC screwed from below in order to run 3-1/2" ventilation ducts. Since the 2x4s only support drywall they can be bisected if ducts need to cross bays--we just use nail plates to protect ducting. This works well except where ducts have to cross pipes or other ducts, so planning is helpful.

Of course this assembly might have one downside in that it doesn't give easy access for future electrical/plumbing/mechanical work the way a full cavity would.

GBA regular and architect Steve Baczek routinely builds down soffits in top-floor hallways to "house" HVAC ducts as well as installing ceiling GWB continuously BEFORE any interior partitions are built. Guarantees a continuous air control layer at the "lid" of his homes.

Peter

Peter,

Thank you for the input and info. You answered an additional question I was going to ask regarding installing ceiling drywall before interior walls go up. This seemed to me like it would be a good way to insure no breaks in the air barrier from interior wall/partition top plates. Now I know I'm not just crazy. :)

Jason,

在你决定之前石膏板天花板the services and interior walls being installed, talk to your sub-trades. It really complicates the sequence of construction.

The framer has to stop while the drywaller boards and tapes the ceiling, then return to do the interior framing - and is now working around finished drywall. The drywaller has to first arrange two deliveries, and then bring in both his boarding and taping crews twice.

The electricians and plumbers are now working blind, unable to see the paths for their runs in the space above, and rather than working off ladders are having to walk the trusses after accessing the attic through a hatch.

It's all doable, and for specialty high-performance builders might make sense, but it's worth exploring the consequences both in terms of time and expense before committing to it.

Malcolm,

Excellent point. What are your general thoughts on the best way to ensure a continuous ceiling air barrier when following a normal construction sequence and building interior walls BEFORE any ceiling drywall?

One thought that I had...

With no interior load bearing walls, could the interior walls be framed with a gap at the top that would allow drywall to still be installed as a continuous air barrier AFTER the interior walls are built?

Jason,

I don't think you need to re-invent the wheel. Either use 6 mil poly, which is much less problematic on ceilings of trussed roofs than it is on walls, or rely on the ceiling drywall, which can be made more airtight by applying gaskets to the top-plates of interior partitions.

值得记住的是,一个通风良好trussed-roof insulated with blown cellulose is a very forgiving assembly. You don't see anything like the problems that commonly occur with cathedral ceilings.

Framing the walls a bit lower and drywalling continuously over top means somehow getting it past the plumbing stacks, wiring and clips connecting the interior walls to the trusses. It also means cutting down all your studs and forgoing any overlapped connections of the top-plates at the exterior.

Another approach to the ceiling service cavity which doesn’t get mentioned often has been described by John Brooks in the first few comments of Joe Lstiburek’s Rules for Venting Roofs article,

//m.etiketa4.com/article/lstibureks-rules-for-venting-roofs

and implemented by Carl Seville and documented in his blog post Topping Out,

//m.etiketa4.com/article/topping-out

as well as by Thorsten Chlupp as described in multiple GBA articles.

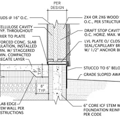

To summarize, minimally sized floor joists are covered with sheathing which is taped to the sheathed exterior walls. Trusses are then set down on this floor deck, and each bottom cord is connected through the sheathing to the joists below. Now the ceiling drywall is not depended upon to act as the ceiling air barrier, and the cavity between drywall and sheathing remains open for services.

The attic floor created does require some extra lumber, but provides the builder a safe deck to work from when setting trusses, installing baffles (custom built 1/4 in. ply of course), adding attic floor insulating, etc., etc.

Any penetrations through the ceiling air barrier are simply and effectively sealed within the attic to the sheathing. And future electrical work would not disturb the attic insulation.

As a owner/builder and DIYer not entirely comfortable up on ladders, the extra time and material would be well worth the safe, solid deck.

Aaron,

There may be situations where it makes sense for DIYers, but as a general proposition I'm not sure it makes sense to add unnecessary materials to a house because the builder isn't comfortable doing routine construction tasks. Especially when the tasks the subfloor will facilitate take such a short time. Setting trusses typically takes a day, baffles shouldn't take more than another one. And there are other drawbacks:

- Depending on the location of interior walls, the spans may mean that even "minimally sized joists" end up needing to be 2"x8"s - or be impractical altogether. The OP's 40 ft span would be impossible using any dimensional lumber. That and the plywood represent not only a considerable expense, but will affect the design of the trusses, which typically aren't make to hold heavy bottom chord loading.

- The joists still only permit duct runs in one direction.

- On a one level 2000 sf house like the OP's, the additional materials - 62 extra sheet of OSB or plywood, and about 1500 lineal ft of joists - are not insignificant. You can rent a lot of scaffolding for the same price, or hire a crew to set the trusses.